Soaring + Handling Risk

How dangerous is flying? Doing a quick Google search, you will find many statistics comparing flying to driving. Here are two YouTube videos that analyze this question, One by Trent Palmer and the other by Nicholas Cyganski.

The general consensus is that driving is safer than general aviation, but commercial aviation is safer than driving.

The two videos concentrate on powered flight, not gliders. How safe is gliding compared to powered flight?

@ChessInTheAir looked at British and German statistics and found that the danger associated with flying a glider on a per hour basis "is about 35x more dangerous than driving; 70x more dangerous than riding a bike, and still 3x more dangerous than riding a motorcycle." Source

The analysis by Professor Martin E. Hellman paints a less bleak picture by comparing driving and gliding on a fatalities per year basis.

There are approximately 5-10 glider fatalities per year in the US and approximately 15,000 active glider pilots, indicating that they bear an annual risk of about a 1-in-2,000 of being killed by participating in the sport. Driving has an annual fatality rate of about 1-in-7,000, so soaring is roughly three to four times more dangerous than driving, on an annual basis. The sport has a danger factor, but one needn't have a death wish to take it up. [Note: There is no way to know the exact number of active glider pilots, so the above number is very approximate.

NTSB Research

By looking at NTSB data, let's learn a little bit more about why gliders crash. Before we start examining this data, I would like to offer my sincere condolences to the friends and family of the pilots we have lost. It is my hope that by analyzing these NTSB reports, we can learn and prevent future pilot deaths.

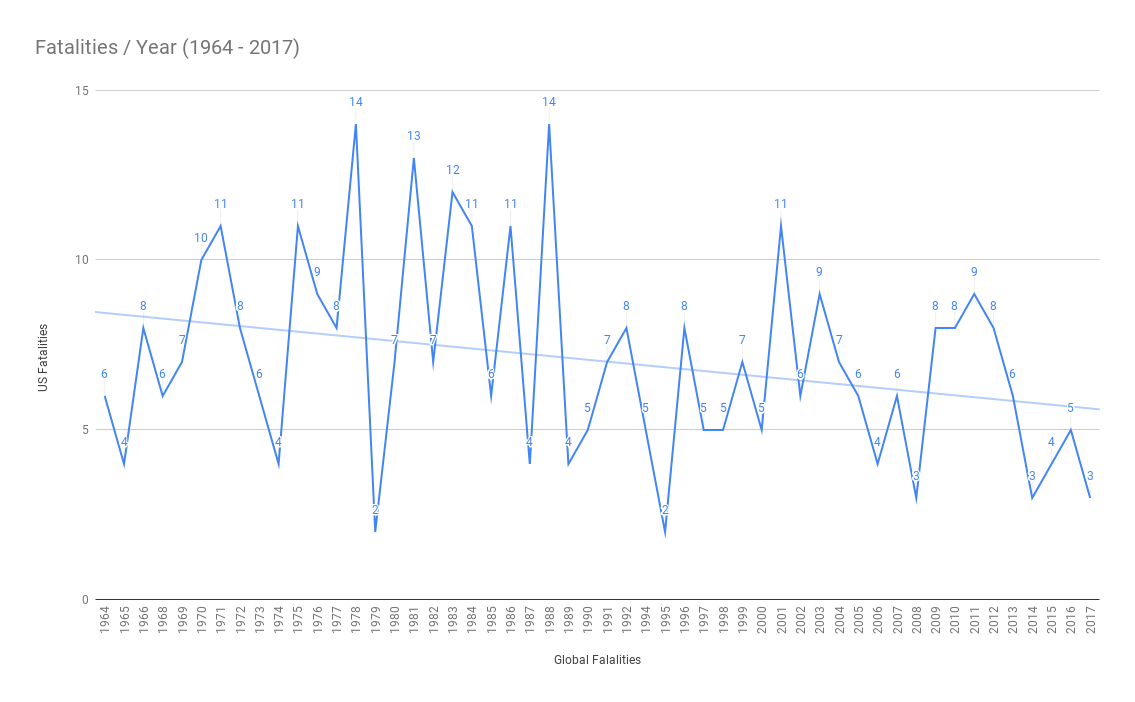

I analyzed annual glider fatalities from 1964 to 2017. Flying gliders has become safer over the years driven by better technology (e.g. FLARM), safety programs, safer competition rules, and better primary training.

Using the same dataset, I plotted the location of glider accidents and we can see they aren't limited to any one location in the United States. However, there is a higher concentration of accidents near mountainous terrain.

View Glider Fatalities in a full screen map

I read and categorized 20 years of NTSB crash data, from 1996 to 2016, where a glider crashed with one or more fatalities. The raw data and my categorization can be found here

Categorizing crashes isn't easy, but there are some high-level patterns. I ended up with the following categories.

- collision - collisions between two gliders or a glider and the tow plane either during take-off or landing.

- free flight collision - two gliders or a glider and a powered aircraft not in the pattern.

- off airport collision - glider colliding with an obstacle, most often during a land-out.

- deployed spoilers - taking off with spoilers deployed.

- downdraft - getting caught in a downdraft, not being able to exit, and impacting terrain.

- failed egress - glider pilot recognized the need to egress but was not able to. I only found one fatality caused by an egress failure and it was due to the canopy knocking the pilot unconscious.

- glider setup - improper setup of the glider. For example, not securing all control linkages or taking off with a tail dolly still attached.

- loss of control - I almost grouped these accidents with stall-spin accidents, but the reports don't specify that the glider stalled. Rather the pilot did not maintain control of the aircraft even before a full stall.

- loss of power - my analysis included motorgliders. These accidents were caused by the engine not performing properly. This category does not include fuel starvation, which I've categorized as glider setup.

- malfunction - rather than improved glider setup, this category includes a true break of a glider control systems. In the 20 year dataset, I found only one accident that fell into this category.

- medical issue - the pilot had a medical emergency (e.g. heart attack or stroke) during flight and loses control.

- uncertified maneuver - pilot attempts aerobatic maneuver in a non-aerobatic glider or attempts a high-speed, low pass to landing.

- unknown - unfortunately, we don't know why some crashes happen.

- vfr into imc - pilot loses control due to disorientation from lack of visual references.

These last two categories are rather vague but really important. * misjudgment - pilot either misjudged a landing distance, chose a poor off-field landing location, or tried to make a ridge when lift was not sufficient. * stall-spin - ok, here is the big one. This is by far and away the most common cause of an accident. With that said, it is often a decision prior to the stall that leads to the glider stalling and entering a spin, but that is very difficult to categorize. Below I've dedicated an entire section to this category of accidents.

Now let's look at phases of flight. To my surprise, free flight, landing, and take-off are statistically nearly equally dangerous phases of flight.

As a side note, my research did bring me across this interesting looking ship, a Kasper Bekas 1-A. Unfortunately, truly experimental and homebuilt aircraft did contribute to pilot fatalities.

Source: dlapilota.pl

Learnings

What can we learn from the pilots we have lost? From my perspective, here are a few things pilots and instructors can do to minimize glider accidents.

-

more abort takeoff training - many of the reports I read involved stall-spin accidents during takeoff. Simulated rope breaks after expensive in both time and cost, but feeling the rope break, learning to get the noise down quickly, and making the correct judgment to land straight ahead or attempt a turn back to the runway saves lives.

-

checklists - many of the glider accidents involved improver glider setup. Sadly, I've found the use of checklists to be more prevalent in the powered flying world. Checklists should go beyond the short before and after takeoff checklists one sees pasted inside trainer cockpits.

-

don't show off - a few of the accidents involved doing uncertified maneuvers or low passes over the airfield. While fun, these are extremely dangerous.

-

draw maps of terrain and hazards - many off airport crashes occurred within a mile of the intended runway. Drawing maps of the surrounding area is a great way to cement hazardous land out spots due to maybe powerlines or fences, and develop procedures when the stretched glide isn't going to get you home.

-

keep banks to 30 degrees or less in the pattern and keep your speed up - inadvertent stalls in the pattern are extremely dangerous. Eliminating distractions, knowing the field, knowing the wind, and keeping safety speed up in the event of downdrafts or wind sheer can help avoid these deadly accidents. "Aiming small and missing small" helps avoid the need for large control inputs.

-

low saves aren't worth it - enough said, relight, and pay the money for the extra tow.

-

don't push it if the lift isn't there. Live to fly another day - ridge soaring is something I've never done but I've been told it is one of the most satisfying parts of soaring. Many of the fatalities in the analysis above were the result of a glider impacting a ridge. Here is a great video of Bruno Vassel making the wise decision to not go for a ridge he is unsure he will make. It cost him a state record, but not his life.

-

FLARM, radios, and ADS-B save lives - many of the mid-air collisions I read about could have been avoided if the pilots had been using radios at the very least.

-

more spin recovery training - more on this below.

Stall-Spins

Stall-spins accidents account for the majority of fatal glider accidents. This is in part because they are the result of something else that is difficult to categories, and also that they most often result in fatalities.

An Analysis of 2008 - 2013 glider accidents by the Northern California Soaring Association does a fantastic job outlining stall-spin accidents and how to avoid them. Typically, a stall-spin on landing looks something like this.

- The pilot stretches the glide to make the pattern and sacrifices airspeed to do so

- The pilot then uses excess rudder to help bring the nose around

- The skidding turn plus the slow airspeed requires correcting the over-banking tendency with reverse aerolon, which increases the angle of attack on the inside wing

- The the slow inside wing at a high angle of attack causes the inside wing to stall and drop

- The noise drops and the pilot then increases back pressure further increasing the angle of attack

- At this point the stall-spin is too develop at an altitude that is not recoverable.

How can we avoid this stall-spin on landing scenario?

- use glide computers to help avoid stretching the glide

- make precise coordinated turns in the pattern

- increase speed in the pattern above best glide--"safety speed"

- limit bank in the pattern to 30 degrees or less

- if too low and slow, and where possible, fly an abbreviated pattern

Wind shear can also catch pilots off guard and lead to a stall-spin. On landing, the wind shear will often increase a pilot's need to bank the glider to remain on the centerline. The bank and the need for opposite airline because of the banking tendency can cause the lower wing to stall.

Handling Risk

The title of this post is handling risk, and it has taken us a long time to get here.

So do we just stop flying? The numbers at the beginning of the post would suggest that the danger is very high.

However, Pilot BB, "Bravo Bravo", posted on a google group back in 2007 and paints the right mentality to approach the risk of flying.

The vast majority of the fatalities among the "extremely experienced" pilots also come down to fairly simple pilot errors -- trying to ridge soar some tiny bump in a strong wind, thermal up off the middle of the canyon, make that last desperate transition, flying over unlandable terrain because "there is sure to be a thermal there" and so forth. More experienced pilots take greater risks. Fatalities from "losing control" or "the plane has failed on them" are essentially unheard of.

So here's the bottom line. Flying gliders is not inherently risky. We only fly in good weather, our systems are very simple, and there is no engine to fail. This rules out 90% of the causes of accidents in light planes. If our pilot training and rules of engagement were the same as that of the airlines, our fatality rate would be less then theirs.

...

The accident-waiting-to-happen takes this fact and says "they were all pilot errors. A truly skilled pilot like me would never do something so stupid." This is a good defense mechanism, but a wiser pilot (or spouse!) will notice that the pilots who crashed felt the same way.

The wiser pilot remembers the temptations to which his much more skilled and accomplished friends fell, and understands "where they failed I could fail as well." He studies obsessively, makes contingency plans and sets personal limits, and runs through his checklist once more.

Astronaut Chris Hadfield echos BB's sentiments: "no astronaut goes into space with their fingers crossed. That's not how we deal with risk." Source In other words, don't play the odds. Rather, prepare, study, drill, set hard limits, and always have a contingency plan.

Other Learning Resources

In the spirit of always learning, here are some other great resources I found while writing this post.

Soaring Safety Videos * https://www.soaringsafety.org/learning/FSvideos.html#thermalstall

Analysis of 2008 - 2013 glider accidents by the Northern California Soaring Association * http://www.airsailing.org/downloads/safety/Glider%20Accidents%20and%20Prevention%20R24B.pdf

DG Blog * https://www.dg-flugzeugbau.de/en/library/potential-dangers-wave

Keep Learning and Fly Safe